Big bomber is watching

Source: Economist

ONE thing that determines how quickly a researcher climbs the academic ladder is his publication record. The quality of this clearly matters—but so does its quantity. A long list of papers attached to a job application tends to impress appointment committees, and the resulting pressure to churn out a steady stream of articles in peer-reviewed journals often leads to the splitting of results from a single study into several “minimum publishable units”, to the unnecessary duplication of studies and to the favouring of work that is scientifically trivial but easy to publish.

There is another way to pad publication lists: co-authoring. Say you write one paper a year. If you team up with a colleague doing similar work and write two half-papers instead, both parties end up with their names on twice as many papers, but with no increase in workload. Find a third researcher to join in and you can get your name on three papers a year. And so on.

To investigate the matter, The Economist reviewed data on more than 34m research papers published between 1996 and 2015 in peer-reviewed journals and conference proceedings. These were drawn from Scopus, the world’s biggest catalogue of abstracts and citations of papers, which is owned by RELX Group, a publisher and information company.

<div class="content-image-float-290…Continue reading

Source: Economist

TO LAND at Indira Gandhi Airport is to descend from clear skies to brown ones. Delhi’s air is toxic. According to the World Health Organisation, India’s capital has the most polluted atmosphere of all the world’s big cities. The government is trying to introduce rules that will curb emissions—allowing private cars to be driven only on alternate days, for example, and enforcing better emissions standards for all vehicles. But implementing these ideas, even if that can be done successfully, will change things only slowly. A quick fix would help. And Moshe Alamaro, a researcher at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, thinks he has one.

His idea is to take a jet engine, put it next to one of India’s dirty coal-fired power plants, point its exhaust nozzle at the sky and then switch it on. His hope is that the jet’s exhaust will disrupt a meteorological phenomenon known as “inversion”, in which a layer of warm air settles over cooler air, trapping it, and that the rising stream of exhaust will carry off the tiny particles of matter that smog is composed of.

Inversion exacerbates air pollution in Delhi and in many other…Continue reading

Source: Economist

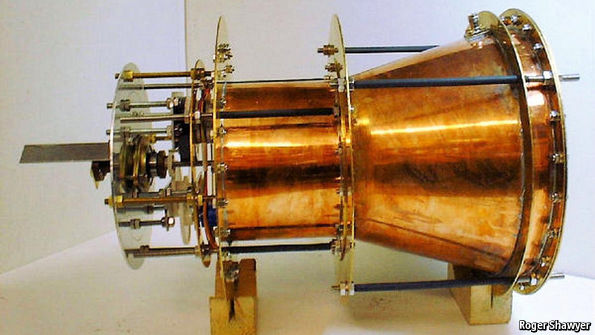

Any reaction?

Any reaction?ROCKETS are spectacular examples of Isaac Newton’s third law of motion: that to every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. Throwing hot gas out of its engines at high speed (the action) thrusts a rocket off its launch pad and into space (the reaction). But having to carry the propellants needed to create the gas (the reaction mass) is a pain, for at any given moment during a flight the action has to propel not only the rocket itself, but also all of the remaining, unburnt propellant. Most of the effort expended in a rocket launch is therefore directed towards lifting propellant rather than payload. As a result, even the most modern rockets start off with a mass that is more than 90% propellant.

The fantasy of rocket scientists is therefore an engine that needs no propellant. And that is what Roger Shawyer, a British aerospace engineer, claims to have invented. In his view, his EMDrive (the “EM” stands for “electromagnetic”) converts electrical energy straight into thrust, with no need for reaction mass. The only trouble is, that should be impossible.

An EMDrive (see picture) is a…Continue reading

Source: Economist

IN THE quarter of a century since the first extrasolar planets were discovered, astronomers have turned up more than 3,500 others. They are a diverse bunch. Some are baking-hot gas giants that zoom around their host stars in days. Some are entirely covered by oceans dozens of kilometres deep. Some would tax even a science-fiction writer’s imagination. One, 55 Cancri e, seems to have a graphite surface and a diamond mantle. At least, that is what astronomers think. They cannot be sure, because the two main ways exoplanets are detected—by measuring the wobble their gravity causes in their host stars, or by noting the slight decline in a star’s brightness as a planet passes in front of it—yield little detail. Using them, astronomers can infer such basics as a planet’s size, mass and orbit. Occasionally, they can interrogate starlight that has traversed a planet’s atmosphere about the chemistry of its air. All else is informed conjecture.

What would help is the ability to take pictures of planets directly. Such images could let astronomers deduce a world’s surface temperature, analyse what that surface is made from and even—if the world were…Continue reading

Source: Economist

HUMANS began planting crops about 10,000 years ago. Ants have been at it rather longer. Leafcutters, the best known myrmicine agriculturalists, belong to a line of insects that has been running fungus farms based on chopped-up vegetable matter for 50m years. By that yardstick even Philidris nagasau, a species of Fijian ant, is a newcomer to farming. It started cultivating plants only about 3m years ago. What distinguishes it is that it is growing not only food, but also homes. It was already known that P. nagasau lives in epiphytes (plants that grows upon other plants) called Squamellaria. But as Guillaume Chomicki and Susanne Renner of the University of Munich describe in this week’s Nature Plants, it also sows and nurtures them.

Dr Chomicki and Dr Renner discovered, in the course of study of the six species of Fijian Squamellaria, that P. nagasau worker ants harvest seeds from their epiphytic homes, carry them away, and then insert them into cracks in the bark of suitable trees. That done, they patrol the sites of the plantings to keep away herbivores, and also fertilise the seedlings as they…Continue reading

Source: Economist

A great hole in Pluto

A great hole in PlutoIS THE solar system about to get another ocean? So far, besides Earth, six bodies are known or suspected to harbour oceans. These are Europa, Callisto and Ganymede (all moons of Jupiter), Enceladus and Titan (both moons of Saturn) and Triton (a moon of Neptune). The latest candidate is Pluto, the most famous inhabitant of the Kuiper belt, a girdle of asteroids that orbit the sun beyond Neptune.

Pluto’s claim to an ocean, argued this week in two papers published in Nature, is based on data collected in 2015 by New Horizons, a robotic spacecraft that zoomed past it in July of that year. The ocean in question, if it exists, is beneath Pluto’s surface. That makes it unlike Earth’s ocean, but like those of the other six bodies. To human sensibilities that is, perhaps, a funny sort of ocean. But add it to the other six and it is Earth’s surface ocean that looks anomalous, rather than Pluto’s buried one.

The argument for a Plutonic ocean—advanced by teams led by Francis Nimmo of the University of California, Santa Cruz, and James Keane, of…Continue reading

Source: Economist

ABOUT 90% of the world’s fish stocks are being fished either to their limit or beyond it. Monitoring fish numbers reliably, though, is no easy matter. Official catch data are often incomplete and sometimes untrustworthy. Moreover, large tracts of the sea are not monitored at all. In order to know which species to conserve, and where, it would be handy to be able to establish fish numbers cheaply and reliably. Now, as they write in PLOS ONE, Philip Thomsen of the Natural History Museum of Denmark, in Copenhagen, and his colleagues think they have taken a step towards this goal.

Scientific surveys of deepwater fish are often carried out by trawling the ocean bed. This means towing a net over a set distance and then hauling it up to count the catch within. That, when due allowance is made for the size of the net’s mouth, yields a figure for the number of each fish species per square kilometre.

Every year a research vessel called Paamiut carries out surveys of this sort in the Davis Strait off south-west Greenland. This year it also had one of Dr Thomsen’s colleagues on board. At each of the 21 places Paamiut dropped her nets, he collected two litres of seawater from the bottom. The team’s aim was not to sample sea life directly, but rather to examine the fragments of floating DNA…Continue reading

Source: Economist