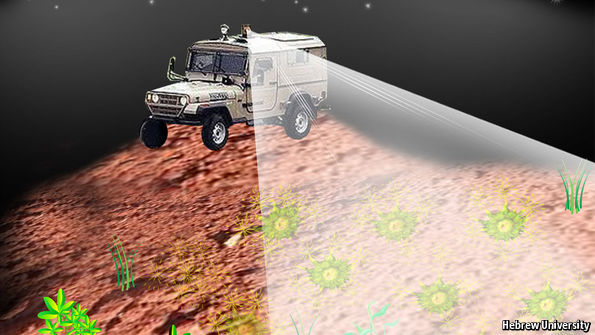

Using fluorescent bacteria to find landmines

BATTLEFIELDS strewn with mines are one of the nastiest legacies of war. They ensure that, long after a conflict has ceased, people continue to be killed and maimed by its aftermath. In 1999, the year the Ottawa Mine Ban Treaty came into force, there were more than 9,000 such casualties, most of them civilians. Though this number had fallen below 4,000 by 2014 it is, according to the Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, an international research group, rising again as a consequence of conflicts in Libya, Syria, Ukraine and Yemen.

These days most mines have cases made from plastic. Only the firing mechanisms include any metal. That means mines are hard to find with metal detectors. Many ingenious ways to locate and destroy them have been developed, ranging from armour-plated machines that flail the land, via robots equipped with ground-penetrating radar, to specially trained rats that can smell the explosives a mine contains. Such methods have, though, met with mixed success—and can also be expensive. Flails, for instance, scatter shrapnel and explosive residue around a minefield, making it hard to confirm that no undetonated devices remain. Minehunting rats, meanwhile,…Continue reading

Source: Economist