Conversational computers

Source: Economist

TAKE a cardboard disc and punch two holes in it, close to, and on either side of, its centre. Thread a piece of string through each hole. Now, pull on each end of the strings and the disc will spin frenetically—first in one direction as the strings wind around each other, and then in the other, as they unwind.

Versions of this simple children’s whirligig have been found in archaeological digs on sites across the world, from the Indus Valley to the Americas, with the oldest examples dating back to 3,300BC. Now Manu Prakash and his colleagues at Stanford University have, with a few nifty modifications, turned the toy into a cheap, lightweight medical centrifuge. They report their work this week in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

Centrifuges’ many uses include the separation of medical samples (of blood, urine, sputum and stool) for analysis. Tests to spot HIV, malaria and tuberculosis, in particular, require samples to be spun to clear them of cellular debris. Commercial centrifuges, however, are heavy and require power to run. That makes them impractical…Continue reading

Source: Economist

The nose knows

The nose knowsONE of a doctor’s most valuable tools is his nose. Since ancient times, medics have relied on their sense of smell to help them work out what is wrong with their patients. Fruity odours on the breath, for example, let them monitor the condition of diabetics. Foul ones assist the diagnosis of respiratory-tract infections.

But doctors can, as it were, smell only what they can smell—and many compounds characteristic of disease are odourless. To deal with this limitation Hossam Haick, a chemical engineer at the Technion Israel Institute of Technology, in Haifa, has developed a device which, he claims, can do work that the human nose cannot.

The idea behind Dr Haick’s invention is not new. Many diagnostic “breathalysers” already exist, and sniffer dogs, too, can be trained to detect illnesses such as cancer. Most of these approaches, though, are disease-specific. Dr Haick wanted to generalise the process.

As he describes in ACS Nano, he and his colleagues created an array of electrodes made of carbon nanotubes (hollow, cylindrical sheets of carbon atoms) and tiny…Continue reading

Source: Economist

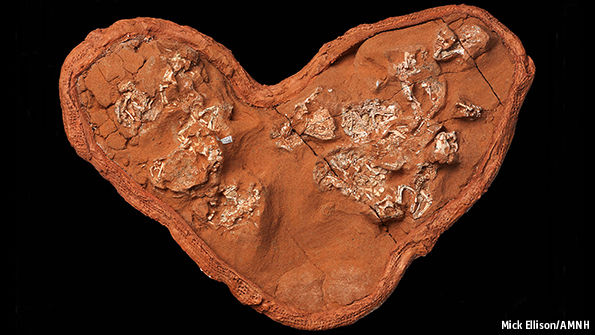

A dinosaur’s nest

A dinosaur’s nestDID dinosaur eggs hatch quickly, like those of birds (which are dinosaurs’ direct descendants), or slowly, like those of modern reptiles (which are dinosaurs’ collateral cousins)? That is the question addressed by Gregory Erickson of Florida State University and his colleagues in a paper just published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. It is pertinent because it touches on the wider matter of just how “reptilian” the dinosaurs actually were. Researchers already know that many were warm-blooded, and that some had insulation in the form of feathers, even though they could not fly. Fast-developing embryos would drive a further wedge between them and their truly reptilian kin.

To investigate, Dr Erickson looked at two sets of fossilised dinosaur eggs. The first, from a Mongolian nest (pictured), was laid by Protoceratops andrewsi, a sheep-sized creature that lived 70m years ago. The second, from Canada, was laid by Hypacrosaurus stebingeri—a species contemporary with P. andrewsi that…Continue reading

Source: Economist

We invite applications for the 2017 Richard Casement internship. We are looking for a would-be journalist to spend three months of the summer working on the newspaper in London, writing about science and technology. Applicants should write a letter introducing themselves and an article of about 600 words that they think would be suitable for publication in the Science and Technology section. They should be prepared to come for an interview in London or New York. A stipend of £2,000 a month will be paid to the successful candidate. Applications must reach us by January 27th. These should be sent to: casement2017@economist.com

Source: Economist

IN A former leatherworks just off Euston Road in London, a hopeful firm is starting up. BenevolentAI’s main room is large and open-plan. In it, scientists and coders sit busily on benches, plying their various trades. The firm’s star, though, has a private, temperature-controlled office. That star is a powerful computer that runs the software which sits at the heart of BenevolentAI’s business. This software is an artificial-intelligence system.

AI, as it is known for short, comes in several guises. But BenevolentAI’s version of it is a form of machine learning that can draw inferences about what it has learned. In particular, it can process natural language and formulate new ideas from what it reads. Its job is to sift through vast chemical libraries, medical databases and conventionally presented scientific papers, looking for potential drug molecules.

Nor is BenevolentAI a one-off. More and more people and firms believe that AI is well placed to help unpick biology and advance human health. Indeed, as Chris Bishop of Microsoft Research, in Cambridge, England, observes, one way of thinking about living organisms is to recognise…Continue reading

Source: Economist

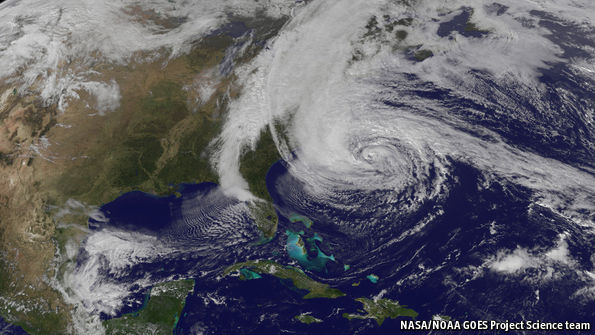

IN 2015, a bit over two years after Hurricane Sandy hit his city, Bill de Blasio, New York’s mayor, announced the creation of a $3 billion restoration fund. Part of the money is intended to pay for sea walls that will help protect the place from future storms.

Building such walls may be an even more timely move than Mr de Blasio thought when he made his announcement. As a paper just published in Nature explains, for the past two decades a natural form of protection may have been shielding America’s Atlantic coast, stopping big storms arriving. Such protection, though, is unlikely to last forever. Mr de Blasio is thus taking the prudent course of mending the roof while the sun is shining.

The study in question was conducted by James Kossin of America’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, using wind and ocean-temperature data collected since 1947. In it, Dr Kossin shows that the intensity of hurricanes which make landfall in the United States tends to be lowest when the Atlantic’s storm-generation system is at its most active.

In Dr Kossin’s view, the cause of this apparent paradox is that, when conditions in…Continue reading

Source: Economist