Dawn of a new epoch?

The start of something new

The start of something newONE way to think of science is as a series of painful demotions. In the 1500s Nicolaus Copernicus kicked Earth from its perch at the centre of the universe. Later, Charles Darwin showed that humans are just another species of animal. In the 20th century geologists found that all human history amounts to less than an eye-blink in the span of a planet that they discovered is 4.6 billion years old.

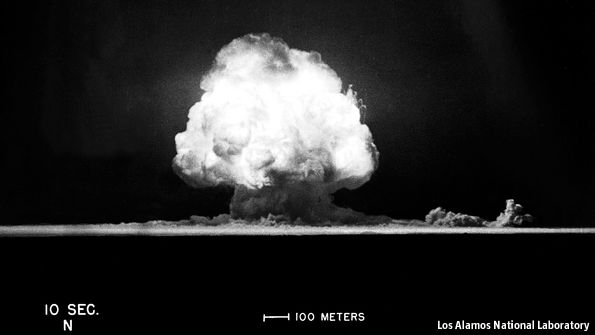

Now, though, those geologists’ spiritual descendants may give humans an unexpected promotion—to the status of geological movers and shakers. On August 29th Colin Waters, the secretary of the Anthropocene Working Group (AWG), an ad hoc collection of geologists, addressed the International Geological Congress in Cape Town. He told his colleagues that there was a good case for ringing down the curtain on the Holocene—the present geological epoch, which has lasted for 12,000 years—and recognising that Earth has entered a new one, the Anthropocene.

As its name suggests, the point of this new epoch would be to acknowledge that humans, far from being mere passengers on the planet’s…Continue reading

Source: Economist