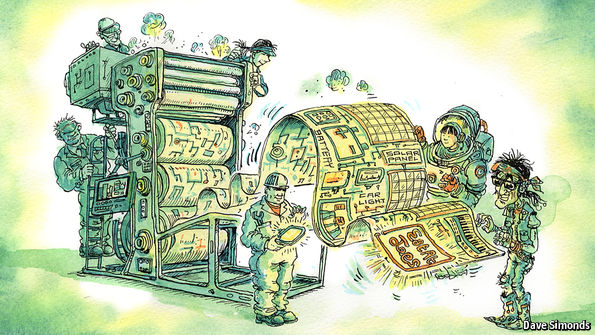

On a roll

MAKING things with 3D printers is an idea that is being adopted by manufacturers to produce goods ranging from false teeth to jet engines. Conventional printing, though, has not remained idle. Machines that have their origins in the high-speed rotary presses that apply words and images to large reels of paper, like the ones which turn out the physical versions of this newspaper, have started making other things as well.

The extent of this transformation can be seen at a factory in Accrington, a town in one of Britain’s former industrial heartlands, Lancashire. Here, Emerson & Renwick, founded in 1918, has expanded beyond its formative business of making wallpaper-printing equipment. The latest piece of kit to which the finishing touches are being added is part of the firm’s Genesis range. It is about the size of a shipping container and is designed to coat and print electrical devices. Like a conventional printer it does so on long rolls of material, called webs. Then, just as printed pages are cut by guillotines from such webs for binding into newspapers, magazines or books, these printed items are cut out and used in products ranging from solar…Continue reading

Source: Economist