Shell shock

Opaque results or translucent answers?

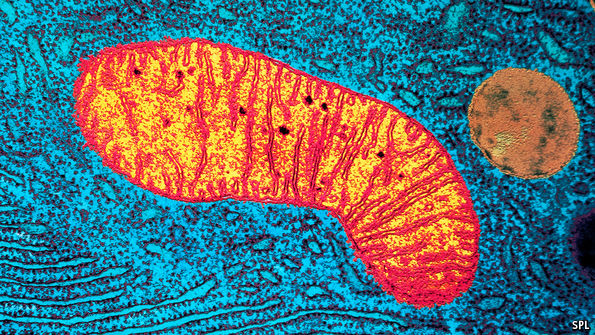

Opaque results or translucent answers?UNDERSTANDING past climates is crucial to understanding future ones, and few things have been more important to that historical insight than fossil foraminifera. Forams, as they are known, are single-celled marine creatures which grow shells made of calcium carbonate. When their owners die, these shells often sink to the seabed, where they accumulate in sedimentary ooze that often gets transformed into rock.

For climate researchers, forams are doubly valuable. First, regardless of their age, the ratio within them of two stable isotopes of oxygen (16O and 18O) indicates what the average temperature was when they were alive. That is because different temperatures cause water molecules containing different oxygen isotopes to evaporate from the sea at different rates; what gets left behind is what shells are formed from. Second, for those forams less than about 40,000 years old, the ratio of an unstable, and therefore radioactive, isotope of carbon (14C) to that of stable 12C indicates when they were alive. That means the rock they are in can be…Continue reading

Source: Economist