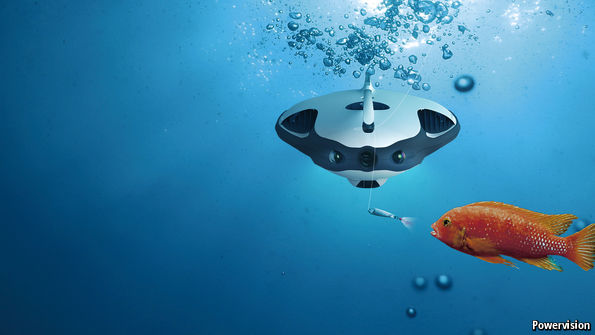

A new Russian weapon may give it an underwater advantage

WHEN introduced 40 years ago, the Soviet Shkval (“Squall”) torpedo was hailed as an “aircraft-carrier killer” because its speed, more than 370kph (200 knots), was four times that of any American rival. The claim was premature. Problems with its design meant Shkval turned out to be less threatening than hoped (or, from a NATO point of view, less dangerous than feared), even though it is still made and deployed. But supercavitation, the principle upon which its speed depends, has continued to intrigue torpedo designers. Now, noises coming out of the Soviet Union’s successor, Russia, are leading some in the West to worry that the country’s engineers have cracked it.

Life in a bubble

Bubbles of vapour (ie, cavities) form in water wherever there is low pressure, such as on the trailing edges of propeller blades. For engineers, this is usually a problem. In the case of propellers, the cavities erode the blades’ substance. Shkval’s designers, however, sought, by amplifying the phenomenon, to make use of it. They gave their weapon a blunt nose fitted with a flat disc (pictured above) that creates a circular trailing edge…Continue reading

Source: Economist