How clean is solar power?

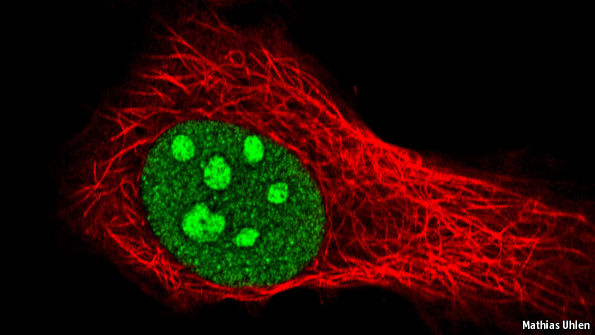

THAT solar panels do not emit greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide when they are generating electricity is without question. This is why they are beloved of many who worry about the climate-altering potential of such gases. Sceptics, though, observe that a lot of energy is needed to make a solar panel in the first place. In particular, melting and purifying the silicon that these panels employ to capture and transduce sunlight needs a lot of heat. Silicon’s melting point, 1,414°C, is only 124°C less than that of iron.

Silicon is melted in electric furnaces and, at the moment, most electricity is produced by burning fossil fuels. That does emit carbon dioxide. So, when a new solar panel is put to work it starts with a “carbon debt” that, from a greenhouse-gas-saving point of view, has to be paid back before that panel becomes part of the solution, rather than part of the problem. Observing this, some sceptics have gone so far as to suggest that if the motive for installing solar panels is environmental (which is often, though not always, the case), they are pretty-much useless.

Wilfried van Sark, of Utrecht University in the Netherlands, and his colleagues…Continue reading

Source: Economist