A new way to classify dinosaurs

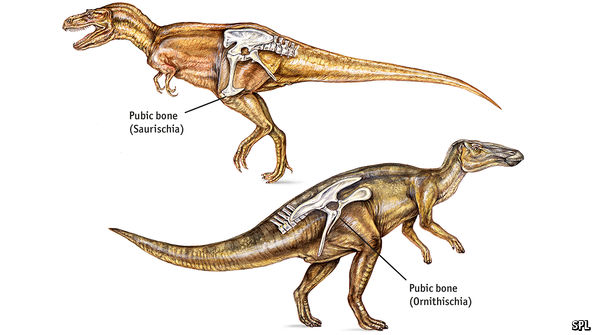

AS EVERY school-aged aficionado of dinosaurs knows, those terrible reptiles are divided into two groups: the Saurischia and the Ornithischia—or, to people for whom that is all Greek, the lizard-hipped and the bird-hipped. The names go back 130 years, to 1887, when they were invented and applied by Harry Seeley, a British palaeontologist.

Seeley determined that the arrangement of the bones in a dinosaur’s pelvis—specifically, whether the pubic bone points forwards (Saurischia) or backwards (Ornithischia)—could be used to assign that species to one of these two groups. In his view, and that of subsequent palaeontologists, the evolution of other features of dinosaur skeletons supported the idea that these two hip-defined groups were what are now referred to as clades, each having a single common ancestor. Seeley thereby thought he had overthrown the dinosaurs as a true clade themselves: he believed Saurischia and Ornithischia were descended separately from a group called the thecodonts.

Subsequent analysis suggests he was wrong about that. The dinosaurs do seem to be a proper clade, with a single thecodont ancestor. But the basic division Seeley made of them,…Continue reading

Source: Economist